Regine Juhls came to Finnmark as a 19-year-old in 1958. Prior to that, she was a child refugee in West Germany during World War II.

She visited the refugee camps on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border a number of times in the eighties together with her husband. The couple took medicines and equipment with them and returned home with elephants and carpets that they sold to raise income for the refugee cause. The strong impressions contributed to a lifetime of engagement.

The devilry had taken over

“We were thrilled; it was a wonderful country with nice people and very few problems. You can’t imagine what it was like then, before all the geopolitical troubles started. We began to see the changes as early as our second visit. “That was when the devilry took over,” she explained. “I was a refugee myself, so it was logical that I was interested in learning how women and children were doing in Afghanistan”, Regine said.

In the yuppie era, people didn’t seem to care

It was difficult to get people interested or involved in Afghanistan in the eighties. In the eighties, the Norwegian people did not want to hear about distress in foreign countries, far away. That’s why we discovered that we wanted to build an oriental space here, to catch people’s attention and give them a beautiful experience,” she said.

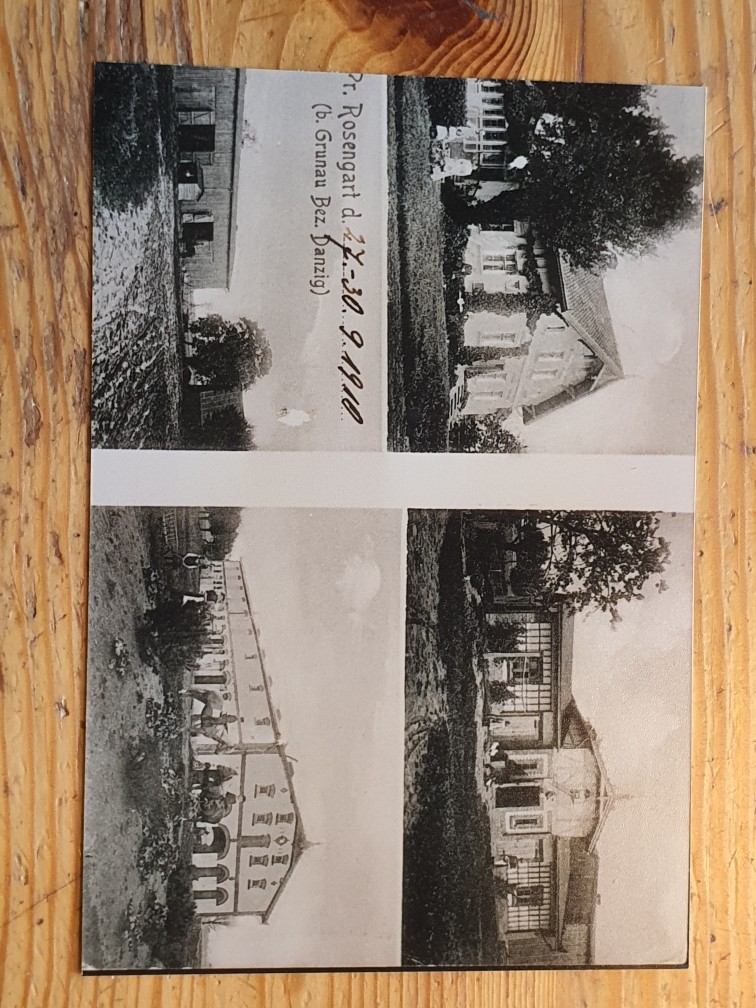

A childhood that began well

Regine was a happy child at Rosengart Farm in East Prussia from 1939 to 1944. The farm had been in the family for 700 years. She became a child refugee at the age of five during the Second World War. “Abandoning the family farm was unthinkable back then. Everything we had was lost,” Regine Juhls told us.

The Russians were coming

Her family feared the Russians at home on Rosengart farm and were monitoring things closely. “My grandfather laid train tracks up to our farm so he could transport grain directly to the farm. My mother put her ear on the train tracks every night to see how far the Russians had come and whether there were any trains going west at all,” Regine explained.

The family was forced to leave everything

Suddenly, one morning, Regine’s mother decided they had to leave. Regine reacted strongly when the coach driver cried as the family left the farm. She had no idea men also cried at times. The driver knew they would never come back. “I thought about the driver crying the whole day,” Regine recalled.

Luckily, they chose to take the road.

The family planned to take a boat from Danzig (present-day Gdansk) to the west, but while they were queueing at the marina, the mother received an important message; “I don’t think you should take those lovely kids on the boat. It would be such a tragic death,” the woman standing next to them warned them. The adults in the travelling party concluded that the crossing was too risky, so they abandoned the queue. And rightly so; the ship they were supposed to sail on went down everyone on board. Everyone died. Regine’s travelling party continued on the road until they reached the western side of the border. The family was assigned a place on the border between east and west.

Regine grew up as a stranger

Regine grew up here as a refugee, with no affiliation to her country of origin. Her family was not integrated into the society they came to. They were isolated and were considered strangers among staunch farmers in the west. Regine couldn’t even walk freely in the hills and pick flowers because the border went through the family field. She felt more and more lonely and unhappy in this new place. She was already dreaming of a society without borders.

Young Regine was enchanted by polar history

Regine devoured everything she came across in books and movies. In 1954, Regine discovered an adventurous life. When she turned 14, she saw Thor Heyerdahl’s film Kon Tiki for the first time. She became deeply fascinated and read everything she found on Norwegian polar explorers and about the Sami people. She was so captivated by Hamsun’s Victoria that she finished it in one night. She didn’t give up until she knew the whole story by heart. Regine dreamed her life away, but she was also very determined. She realised right away that she had to get away from the farm. Regine wanted to travel north to Norway and the land of the Sami (Sàpmi). She wanted to experience Arctic nature and Sami culture first hand.

Regine Juhls decided to travel north, against the will of her parents.

The young girl left her family without a penny, with one goal in mind, to make her way north to Finnmark. She wanted to meet the Sami people she had read so much about in books. During a short stay at a theater college in Vienna, Regine headed north to Oslo, against her parents’ wishes. After staying a short while in Oslo, her journey continued on foot across the mountain to Bergen. She slept in the wild and spent the night in open cabins. She brought some food with her but she ate berries and drank fresh water from brooks and streams along the way.

Young and determined, she kept the land of the Sami in her sights

When Regine arrived in Bergen, she went straight down to the quay and was hired on the Hurtigruta coastal steamer heading north – with the last stop in Tromsø. Before she reached Sápmi, she wanted to show the Sami that she knew their history, so she sat down at the library in Tromsø and read before she left. After arriving in Alta a few weeks later on a fishing boat, she was able to continue across the plateau to Kautokeino by snowmobile. Finnmark was deserted back then, still an inaccessible wilderness in the late 1950s.

She spent an entire winter on the plateau with a Sami family

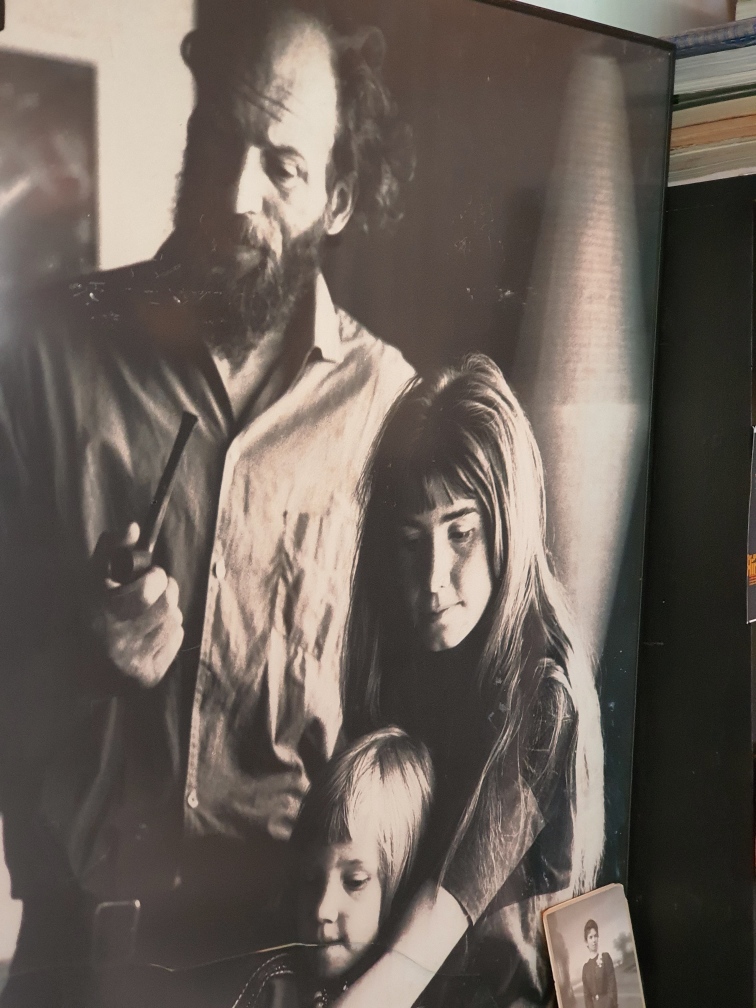

Regine got in touch with a Sami family that invited her to live with them via her travelling companion, a female teacher. In Kautokeino, she got in touch with a Danish man who lived in a cabin by the river. Frank Juhls was an artist and worked as a handyman for the Sami. Regine accompanied the nomadic Sami family as they followed their reindeer herd across the plateau for an entire winter.

A pile of love letters awaited her in Alta

When spring came, she had originally thought of going home to West Germany, but in there was a pile of love letters waiting for her in Alta. All the letters were from the Danish man she met in Kautokeino the autumn before she entered the mountains. This inspired her to return to Kautokeino where she found the man of her life.

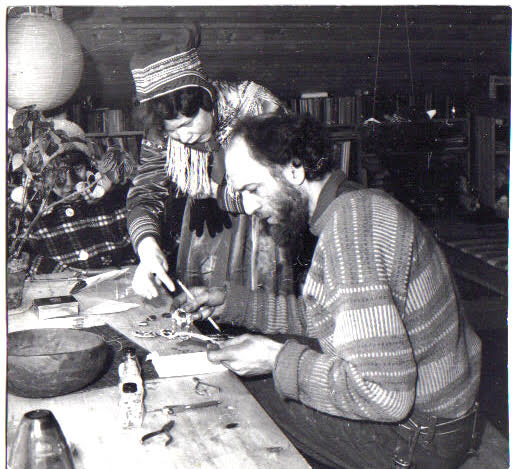

Her learning curve was steep in the jewellery trade

Regine Juhls learned how to fashion jewellery in record time together with her Danish husband Frank Juhls at a jeweller’s in Copenhagen. She worked diligently at home in Kautokeino, becoming a leading jewellery artist in Norway in the sixties. She created iconic jewellery where tradition met the present. Jewellery that stands by virtue of its timelessness and fine handicraft. Jewellery symbolises tradition, culture and history.

Solidarity with refugees lives on

Art, culture, crafts and solidarity go hand in hand in a business deeply rooted in Sami traditions while being innovative and attractive. The employees are both cultural mediators and craftsmen. The Juhls silver shop is one of very few jewellery workshops of its size still in Norway. Regine Juhls is committed to solidarity and more interested in refugees than ever before. She is committed to helping displaced people move on with their lives. Regine’s history touches both employees and visitors.