The spring aurora season ends with a grand finale! The end of March and beginning of April could be the best chance to experience the strongest northern lights in many years for two reasons. First of all, there are usually much stronger auroras around the spring equinox. In addition, the activity on the Sun, which controls the frequency and strength of the aurora, is also higher than it has been in almost 20 years. Furthermore, at the end of March the nights are still dark, allowing you to observe the aurora. Thus, this spring will be a perfect time to visit North Norway and experience one of nature’s most spectacular light phenomena.

The auroras are born on the surface of the sun

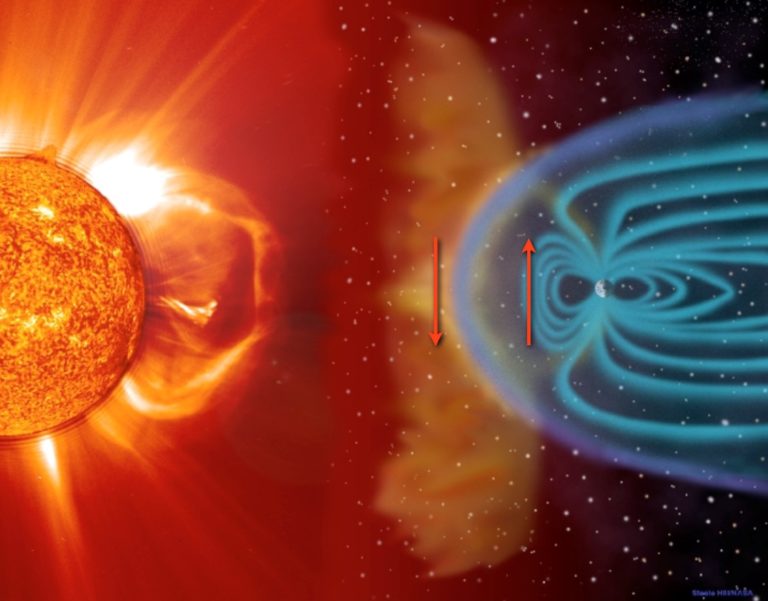

The source of the aurora was first explained by the Norwegian scientist Kristian Birkeland more than 120 years ago. He was the first to argue that the Sun sends out a stream of charged particles that interact with Earth’s magnetic field. These particles, consisting of protons and electrons, are called the “solar wind.” Earth’s magnetic field creates an invisible shield around the planet that prevents our atmosphere from being bombarded with solar wind particles. We call this magnetic cocoon engulfing Earth the magnetosphere, which normally protects us from solar particles.

Geomagnetic storms are brewing

The solar wind and solar storms also carry with them the magnetic field of the Sun. This magnetic field will interact with Earth’s magnetic field and create what we call a geomagnetic storm, which fuels strong auroras. Here lies the key to understanding why auroras are stronger and more frequent around the equinoxes.

Opposite magnetic fields create the magic

You know that a magnet always comes with two poles: a north pole and a south pole—just like a compass needle. Solar magnetic fields—carried to Earth via the solar wind—also have a north and a south pole. South-pointing magnetic fields inside the solar wind oppose Earth’s north-pointing magnetic field. The two oppositely directed magnetic fields partially cancel each other, weakening our planet’s magnetic defense. This opens up holes or cracks in the magnetosphere, allowing solar particles to flow more easily toward the polar regions, where they eventually collide with atoms and molecules in our atmosphere, creating the dazzling northern lights. However, if the magnetic field in the solar wind has a northward-directed orientation, there will typically be very weak interaction and low aurora activity.

The model dates from the 70’es

The scientists Christopher Russell and Robert McPherron explained this cancellation effect in the 1970s. The cancellation of the magnetic fields can happen at any time of the year, but it occurs with the greatest effect around the equinoxes. They put forward a model to explain why these holes in the magnetosphere open more frequently around the equinoxes. Thus, the effect is today called the “Russell–McPherron effect.”

It’s about tilting the right way..

Their model points to the alignment of Earth’s magnetic field. Just like Earth’s tilted rotation axis, it is slanted with respect to the Sun and our orbit around it. Twice a year, around the equinoxes, Earth’s orbit brings this tilted field into a prime position to receive charged particles from the Sun, generating strong auroras.

Furthermore, it is known that at the equinoxes Earth’s magnetic poles fall at a right angle to the direction of the solar wind’s flow, making the solar wind more potent. This also leads to more frequent geomagnetic storms and more auroras. This effect is called the “equinoctial effect.”

To add to the above-mentioned effects related to the equinoxes, the current high activity on the Sun will fuel even more northern lights this year and in the coming years.

Every eleven years, the sun’s heart beats

The Sun has a heartbeat. Every eleven years or so it beats, and it beats hard. This is known as the solar cycle and is measured by the number of sunspots visible on the Sun. Thus, every 11 years the Sun undergoes a period of high activity called the “solar maximum,” followed about five years later by a period of relative quiet called the “solar minimum.” During solar maximum there are many solar storms, and during solar minimum there are few.

We’re just past the maximum

Aurora activity varies with solar activity, which reached a maximum in 2025. Furthermore, it turns out that the peak of aurora activity comes a few years after solar maximum. This means that the coming 2–3 years will be unusually good for experiencing strong auroras dancing across the night sky.

Thus, if you travel to North Norway this spring, you will have a great chance to see more northern lights than in many years.

What are the Northern Lights

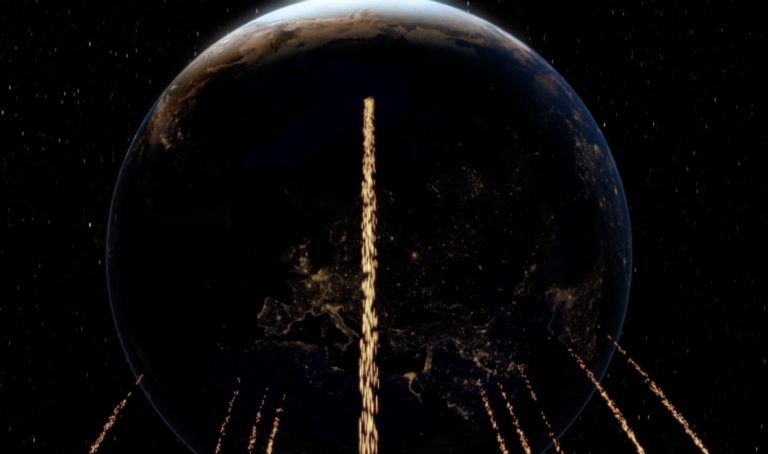

The solar particles that manage to enter Earth’s magnetosphere are guided along the magnetic field lines down toward the polar regions. When they hit Earth’s atmosphere, they collide with oxygen and nitrogen. These collisions, which typically occur at altitudes between 80 and 300 km, transfer some energy to these atoms (they get excited) and immediately send out light at a certain frequency or color. When billions of such small flashes occur each second, the cumulative effect is a spectacular glowing atmosphere with green, red, white, and blue colors.

The mechanism that makes the sky glow is very similar to what happens in a light tube, neon sign, or an old-fashioned TV set. The mechanism behind the aurora is well described in the book The Story about the Northern Lights and the documentary Northern Lights – A Magic Experience, which can be downloaded here: www.solarmax.no

Pål Brekke is a solar physicist with a PhD in astrophysics from the University of Oslo. Ha has worked for many years at NASA. He is currently lead space science at the the Norwegian Space Agency. Pål Brekke also takes an interest in popularising astrophysics and Northern Lights, and is a much used lecturer and author of Northern Lights publications for a wider audience. He has also produced an award-winning documentary about the northern lights. Read more about his work on the northern lights at www.solarmax.no.

This article is written by Pål Brekke, who also made the scientific illustrations. However, the “Helpful hints for planning” is written by the editing team of this website.

Helpful Hints for Planning

The spring equinox means that day and night are equally long. This, in turn, means longer days, perfect for exploring the beautiful landscapes of the north and for outdoor activities such as skiing, dog sledding, ice fishing and snowmobiling. More stable weather also means calmer waters, ideal for fishing and kayaking. In town, locals enjoy al fresco coffee, albeit with mittens on. The overall atmosphere is very different from the short days and low light of mid-winter.

In short, the weather is milder and more stable than in early and mid-winter. The skies are clearer; there is less wind and fewer storms, and temperatures tend to be higher. In coastal areas, you can expect daytime temperatures hovering around zero, maybe a bit above, although it can be colder inland. Nights are still freezing, though, especially if the weather is clear. Snow is guaranteed, except perhaps in archipelagos out at sea. In large parts of Northern Norway, late March and early April see the deepest snow of the whole winter, before mild spells in April trigger the start of snowmelt.

Actually, since the Atlantic has cooled down, there is less evaporation taking place. This means that the chances of clear skies are the best of the entire Northern Lights season, which of course increases your chances of seeing the Northern Lights.

If you come in late March, you have excellent chances of spotting the Northern Lights, as nightfall still occurs around 6–7 pm. However, around the beginning of April, daylight hours start to eat into the best evening hours. You still have good chances, partly because of the Russell–McPherron effect, although these diminish with each passing night. By mid-April, however, the chances are decidedly slimmer, and any display is a bonus.

Busted! Yes, you probably did. We do publish a similar article for the autumn season as well. The Russell–McPherron effect is, in fact, exactly the same phenomenon in spring as it is in autumn.

In agreement with the author, Pål Brekke, we have nevertheless chosen to present two separate articles. A Northern Lights trip to Northern Norway based on the Russell–McPherron effect takes place in a very different context in terms of weather, daylight and overall atmosphere depending on the season.

So yes — to be completely honest, it is largely the same science presented twice, just wrapped slightly differently to reflect two very different seasonal experiences.