Engnesodden on Skjervøy is a scenic viewpoint overlooking vast fjords, the shipping lane, and the mountainous islands of Northern Troms. The promontory itself is scattered with the remnants of a blown-up World War II coastal fort. The hike there follows a forest path high above the fjord and is easy to manage.

In early June, you can encounter spring, summer, or even a hint of winter; I was moderately lucky. The air was cool, and light raindrops hinted at a downpour that never came. Tongues of snow streaked the mountainsides, separated by patches of bare earth. Down in the lowlands, the trees were bursting into life — birch trees wore tiny “mouse ear” leaves, and the rowan’s larger leaves were beginning to unfurl.

After a quick explanation from the hotel receptionist, I walked uphill through the neat residential streets of Skjervøy. Just above the football ground, I spotted the lighting masts of the ski track. They guided me out of the little town and into low-growing birch forest — exactly as I had been told.

The trail leads into the forest

Soon, I felt enveloped by the forest. The low, wind-bent trees gave way to denser growth, and before long I reached a viewpoint with sweeping views eastward into the harbour of Skjervøy. The protective jetties and the neat little town, its houses arranged in terraces around the port, made a charming sight.

I carried on, catching glimpses of the sea through the foliage. Rounding a bend, I was surprised to find snow on the trail — a patch that had clung on into June in the shade of a north-facing slope.

A brook added its voice to a hillside carpeted with last year’s leaves. The trail skirted the edge of a small tarn, hemmed in by steep banks. Down in the moss, where plants and insects were still mustering courage to emerge, the dark water and soft green surroundings felt like something from a Japanese woodcut.

I could see far and wide

The trail kept bending left until the forest opened onto a sweeping panorama. To the west rose the towering, sheer slopes of the mountainous islands of Laukøya and Arnøya, their peaks — some over 1,000 metres high — lost in the fog. Straight ahead, the fjord widened, and far in the distance I could just make out the mountains marking the border between Troms and Finnmark.

To the east, however, the island of Haukøya was bathed in unexpected sunshine. Beyond it, the jagged Kvænangstindan — the “dragon’s back” — thrust their pointed peaks into battle with the clouds. From here, the beauty of the view is matched only by its history: at the very tip of the headland ahead lies the crumbling remains of a Second World War coastal battery, silent now but once a place of watchfulness and war.

A military fort rose from the landscape

The military-looking structure sparked my curioused. Scanning the shoreline of the promontory below, I spotted a block-like shape perched on a rise. From the viewpoint, I could trace a grassy wheel track winding down towards it. My feet grew wet in the tall grass as I descended.

Circular gun emplacements — deep, walled pits — lay silent, their crumbling concrete and rusting rebar speaking of another time. This had once been a place teeming with people, orders, and urgency. Down by the shore, green meadows waited for the Arctic summer, while broken foundations marked where buildings had stood. On the way back up, I peered into dark caves carved into the hillside, their silence as heavy as the history they held.

I was on the Atlantic wall

In 1940, the German Reich established military control from the Norwegian–Russian border all the way to France’s frontier with Spain. Britain, however, refused to yield, and to secure its grip on occupied territory, Nazi Germany fortified the entire coastline with bunkers, observation posts, and gun emplacements — the so-called Atlantic Wall.

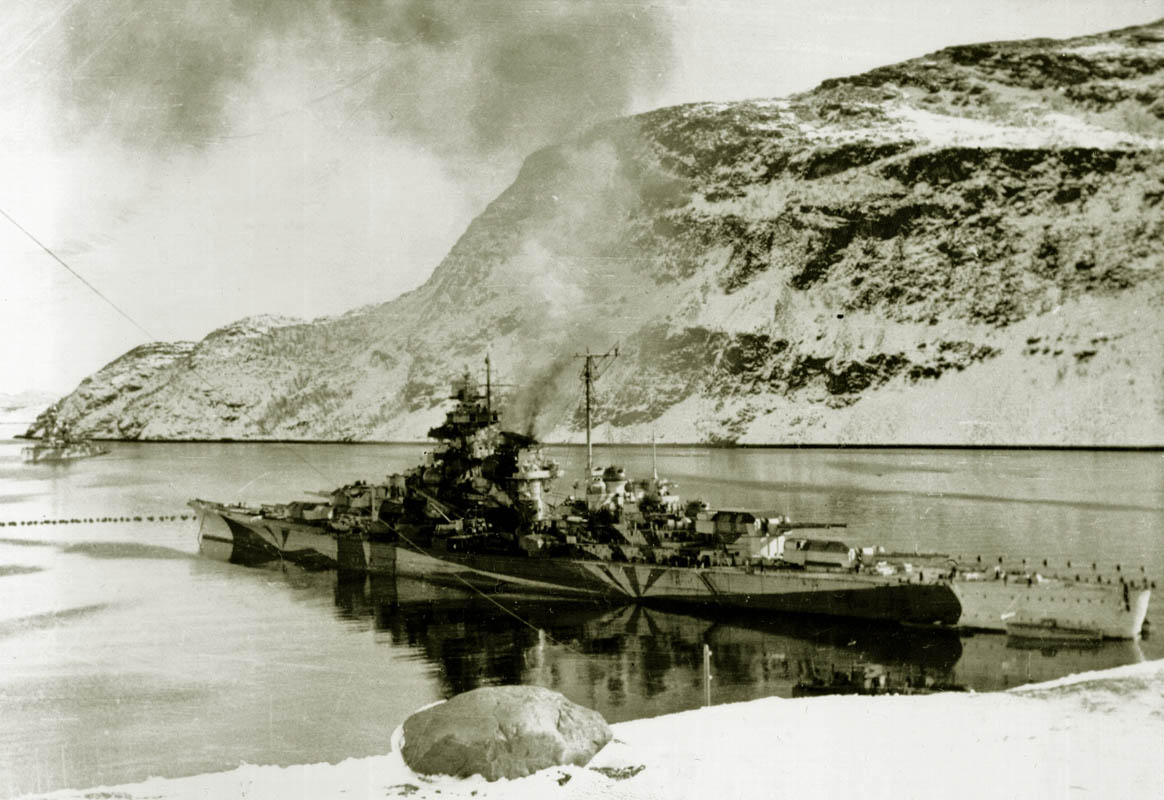

The sweeping view I had just admired was once part of this vast defence network. From Engnes, German forces could monitor a long stretch of Norway’s coastal fareway. The entrances to two major fjord systems — Kvænangen and the deep Lyngenfjord — lay within sight, both of strategic importance. Out in the open Atlantic, the British navy harassed Nazi shipping, while far to the north, the legendary Murmansk convoys fought their way to Soviet ports. Small wonder Engnes bristled with fortifications.

Six guns could shoot 17 kilometres

The coastal battery at Engnes was started in 1942 and declared operational in January 1945. It consisted of six gun positions with artillery capable of reaching up to 17 kilometers, along with anti-aircraft and searchlight installations. The battery included several concrete bunkers, trenches, and shelter rooms, as well as underground rock chambers for ammunition and personnel.

The gun positions were placed in deep concrete pits with storage niches for ammunition, and trenches connected the positions, allowing soldiers to move protected between them. In April 1945, the German withdrew from the area beyond a new defensive line north and east of Tromsø, the guns and ammunition were transported away and the command centre blown up.

Soviet prisoners paid the heaviest price

The builders of the coastal battery were Soviet prisoners of war, held in a camp established on Skjervøy. These prisoners were forced to construct the coastal defenses and roads, including the route leading to Engnes. They endured harsh conditions, living in simple, uninsulated huts and surviving on meager rations. Many attempted to escape but were often caught and severely punished, with some executed.

Though the camp was destroyed in the last days of the war, remnants such as building foundations and a guard tower can still be seen today — silent reminders of the suffering endured here during the war.

I returned the same way

Along grassy paths, I retraced my steps back to Skjervøy. There’s a longer route you can take, but I felt I’d had enough for the day. On the way, I finally met a few locals walking their dogs in the evening calm. Back at the viewpoint overlooking Skjervøy, I noticed the Hurtigruten — now often called the Coastal Route — approaching the harbour. I lingered a while to snap a photo. My walk was peaceful and calm — a stark contrast to the challenges faced here 80 years ago.

Facts about Engnes and Skjervøy

Engnes is a promontory marking the northern tip of the island of Skjervøy, where the Nazi occupiers built bunkers and fortifications during the second world war. It is found some 3-4 km on foot north of the little town on Skjervøy, mid way between Tromsø and Alta in Northern Norway.

You can do two things: Either walk from Skjervøy to the Engnes promotory, and return the same way. Or make a little detour uphill to Skjervøytrollet, some 200 metres high. All in all about 8 m or two hours.

Skjervøy is a fishing village on the coast of Northern Norway. It is some 3,5-4,5 hours’ drive from Tromsø, and some 3 hours from Alta. From Tromsø you can take the Hurtigruten/Havila ship, taking some 4 hours. There is also a comfortable catamaran most days of the week, along with a bus connection.

Skjervøy is decidedly untouristy, but there is a mid-range hotel and some simpler accommodation. Consult the website of Visit Lyngenfjord.

The hotel has a restaurant, and there are a couple of options along the main street. Do note that dinner is served early in Skjervøy. Consult Visit Lyngenfjord for the details.