Seventy five thousand people were forcibly evacuated from Finnmark and Northern Troms in 1944-45, 25 000 of whom fled to the mountains. Robbed of their visible history, after the war the people of Finnmark built a new, modern society with new ideals. The Museum of Reconstruction tells the story of the forced evacuation, cave-dwellers and post-war reconstruction, and you may find yourself shedding a tear along the way.

Before World War II, the regions of Finnmark and Nord-Troms were inhabited by three different, distinct ethnic groups: the Sami, the Finns (Kvæn) and the Norwegians. Some were still living in turf huts under the same roof as their livestock. Others lived in Finnish-style log cabins or in log houses prefabricated on the shores of the White Sea in Russia and sold as building kits to the fishing villages along the coast. The “better” parts of Hammerfest and Vardø featured the colourful, painted wooden architecture of the Norwegian inhabitants. The new industrial town of Kirkenes represented modernity. All in all, pre-war Finnmark was not only multi-ethnic but the people’s livelihoods spanned the entire spectrum from ancient barter economy to modern industrial society.

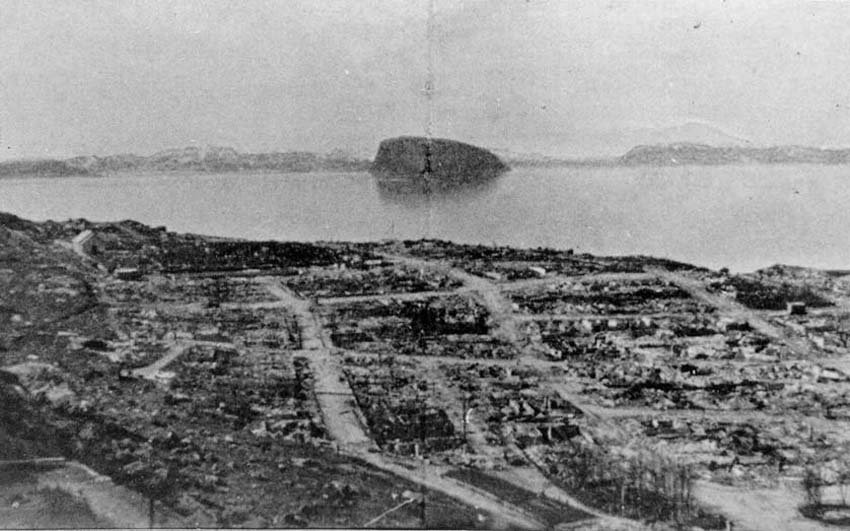

People were evacuated before the town was burnt to the ground

In 1941-44, the fighting in Finnmark was limited to Eastern Finnmark, to the area close to the front line. However, in the autumn of 1944 the Soviet Union managed to advance and pushed the front over into Norwegian territory at Kirkenes. In response, the German occupying forces decided to establish a new front line between Lyngenfjorden and the Swedish border. An order for forcible evacuation of the civil population was given for the area east of Lyngenfjorden. The houses were to be razed to the ground, the bridges blown up and the infrastructure destroyed, so as to leave nothing for the Soviet army.

Practical questions about the musuem

You can find more information at the great museum website.

You can visit the Visit Hammerfest site with information on things to do in the city including tours, places to eat and drink, sights to see and places to stay.

Nearly all buildings were raised to the ground

In Eastern Finnmark the evacuation went extremely rapidly, with insufficient time to destroy everything, and so some of the pre-war buildings were preserved. However, in Western Finnmark and Northern Troms down to Manndalen in Kåfjord the destruction was almost total. Eleven thousand houses, 350 bridges, 22 000 telegraph poles, 27 churches; human civilisation disappeared from the surface of the earth.

Evacuation was a swift policy

Fifty thousand people were forcibly evacuated. Most were transported by ship to Tromsø, and from there sent further south, where they were billeted in other people’s homes. The evacuees were only permitted to take a rucksack or suitcase with them. Some buried their furniture and valuable objects, but by and large people lost everything they owned.

Thousands moved to the mountains and hid in caves

The Norwegian government in exile in London made radio broadcasts urging people to oppose the forced evacuation, and about 25 000 tried to escape. They made off to the mountains and hid in caves. Not anticipating that they would have to fend for themselves for the entire winter, they thought the Allied Forces would quickly come to their rescue. Pregnant women, children and old people spent the whole winter in the caves; the wisdom of the appeal made by the Norwegian government in London has subsequently been questioned.

Government reconstruction plans were too slow for the locals

When peace came, the Norwegian government wanted to reconstruct and restore Finnmark and Northern Troms before allowing the population to return. Owing to the harshness of the climate, the presence of mine fields and a total lack of infrastructure, the authorities believed that an overall plan and a direction for the reconstruction were essential. But the people of Finnmark could not wait, and began returning home under their own steam already in the summer of 1945.

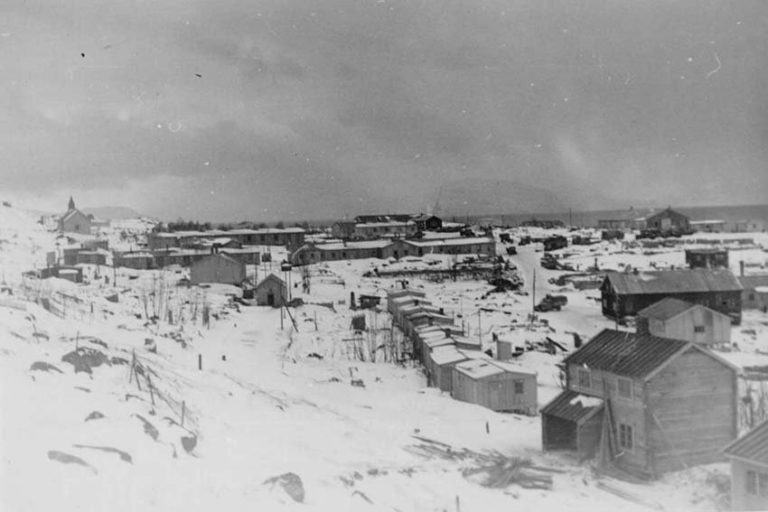

All kinds of shelter became home

When the people returned to Hammerfest, they were unable to recognise the street grid or to identify the foundations of their own houses, so thorough was the destruction of the town. The first winter in Finnmark had to be spent living in tents, sometimes reinforced with planks from German aircraft runways. Some people lived in up-turned boats, and others in the good old turf huts. After a while wooden barrack-like structures were built, in which a whole family would live in a single room without water or electricity.

Reconstruction was swift and architecture modern

The post-war reconstruction of Finnmark and Northern Troms was a huge effort for the Norwegian nation. For the latter half of the 1940s, the people of Finnmark lived in shacks, huts and barracks. Then, in the 1950s, towns, fishing communities and villages were reconstructed with modern, standard house types, a style of architecture that still dominates the far north of Norway. This meant a fantastic improvement to the standard of housing, and in the 1970s houses and apartments without a bath and WC were far more common in the east end of Oslo than they were in Finnmark.

Everyone had to start over from scratch

Not only were the old houses gone, so too were most people’s furniture, equipment, household goods and utensils. Everyone had to start again from scratch. The reconstruction was characterised by a desire to disseminate a modern lifestyle, including ideals of how the modern home should be furnished. Sami and Finnish (Kvæn) culture and ways of life gradually came to seem old-fashioned and without value, and the people of Finnmark became more alike and more “Norwegian”.

The museum’s tower show a photographic history

The Museum’s tower, houses a separate exhibition of photographs of towns, fishing communities and villages both from the pre-war era and the post-war reconstruction. They show clearly how the cultural landscape of Finnmark was transformed from a diverse, multiethnic and distinctive architecture to a uniform, homogenous post-war look.

The Museum of Reconstruction

The Museum of Reconstruction in Hammerfest (Gjenreisningsmuseet) gives a broad presentation of all these facts. The scene on Constitution Day, 17th May 1945, in the ruins of Vadsø is starkly contrasted with the scenes of joy in Oslo; we see the barber’s chair from Hammerfest brought along to the south and the swastika-patterned christening robe of the child of a German soldier and a girl from Sørøya: all these glimpses of individual human fates shine through the black-and-white images, display cases and models. In every way, the museum gives an objective, thoroughly prepared, nuanced and balanced telling of the story, but visitors are both affected and moved nonetheless.