A storm was about to die down as I came to Elgsnes, blowing the last of an exceptionally long Arctic summer away. Undeterred, Tore Ruud welcomed me in wellingtons, and took me around as the trees were swaying and the wind was whistling around the 1723 main house of Elgsnes. A historic walk was to begin, moving elegantly between the millennia in a landcape of mountains, coastlines, farmland and forest.

Elgsnes is remote, but used to be in the middle of things

Elgsnes is located on the tip of a narrow peninsula just north of the city of Harstad, on the island of Hinnøya. The road there is a winding one, taking you up and down the Aunfjellet mountain. It all feels off the beaten track, and very traditional. Not so long ago, though, Elgsnes took centre stage. The Toppsundet waterway between the islands of Hinnøya and Grytøya is part of the main highway for maritime transport in the north. Before the advent of boats with engines – the transition happened around 1900 – sail-powered fishing boats could be pulled up on shore at Oppsetta, a sheltered part of the Elgsnesvågen bay. In much earlier times, when the sea level was higher, fish, walruses, seals, birds, and eggs drew Stone Age people to this place. The gale blowing was apparently the wind of history.

The stately house dates from 1723

Built in 1723, the main building at Elgsnes is a gem. Built at the promontory called Raten, it overlooks the Toppsundet waterway, and is clearly visible from sea. Selling stockfish out of Northern Norway and importing goods from the south and abroad used to be a privilege for burghers of Bergen or Trondheim, and the Norman family from Trondheim was given the right to trade at Elgsnes in 1675. For long, the traders were at Elgsnes in the summer and stayed the winter in Trondheim. By 1793, they were living permanently at Elgsnes, and in the first half of the 19th century, the trading post had its richest period. In this period, the trading post hosted elegant soirées for the right kind of people.

The place was once filled with houses

Tore showed me a drawing of the trading post from 1870. The stately house, painted in a distinguished white, dominated. But there was a multitude of smaller houses, like a shop, a kitchenhouse for the staff, a fish drying shed, a barn, a stable, a shed for the fishing nets – a small village was spread around the headland. However, the economy shifted. Other trading posts benefited from the rich herring fishing at the time, and by 1881 the trading post was bankrupt. New owners turned to agriculture, but Elgsnes was no longer the centre of things. We walked around the promontory and looked at barely visible traces of the houses.

A Bronze Age grave holds a prominent location

As the water was higher some millennia ago, the Raten promontory was a small island. At its highest point, the Masterhågen, there are remains of a stone heap, which undoubtedly was much higher before the stones were used for building. This is probably a grave from the Bronze Age, on a position clearly visible from the sea. Another Bronze Age grave, now lost, has been reported on the promontory across the wide bay, Vester-Raten. It all points to connections to the Bronze Age cultures of Southern Scandinavia. We must imagine this to be the grave of someone important a society with more pronounced social differences than before.

Follow the beach to the ship landing

We walked down to the lovely beach, popular among the people of Harstad on warm summer days. Today, the waves were pounding towards the beach, but not nearly as intense as we could observe outside the sheltered port. At the end of the beach, big rocks surround the Oppsetta landing. Here, boats were hauled ashore over centuries, from before the Viking Age to the introduction of boats with fuel-powered engines.

The field hides many graves

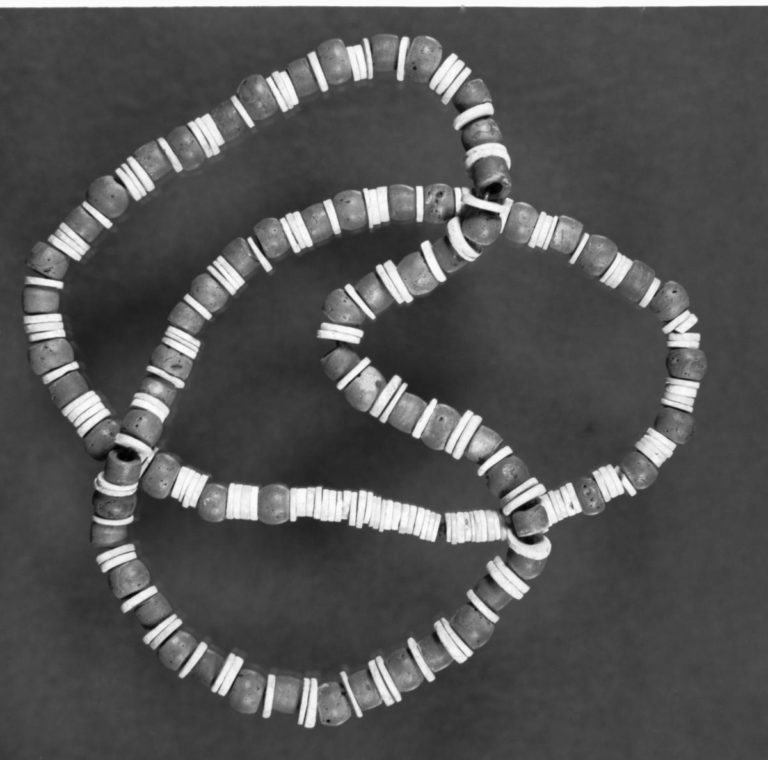

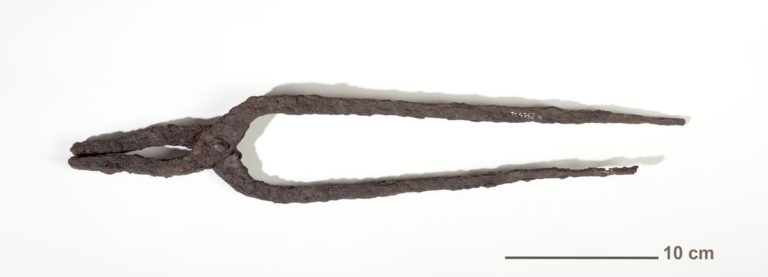

When Tore and his siblings helped out harvesting potatoes as kids, it wasn’t uncommon to find old things in the field. This caused a welcome distraction from the hard work. And indeed, the field is full of graves. A man from the Early Iron Age had been buried with his sword, as well as a precious amber bead for his journey to the next life. The rich grave from the Merovingian phase of the Iron Age – 6-800 aD – must have been of a woman of high birth. More than 200 pearls made from walrus tusk, glass and terracotta, brooches – including one of Eastern Finnish origin – were among the riches in her grave. Other useful items for the afterlife included a comb, a key, a pair of sheep shears and even some tweezers.

A blacksmith took his tools to the afterlife

We walked slowly up the little road across the field. The grave of a 40-year-old man, some 172 cm tall, and strongly built, was also found here. A wooden box with iron nails was found next to his head, filled with tools. A hammer, a chisel, an iron file, a whetstone, a pair of tongs… all a combined blacksmith and carpenter would need. The man had a stiff ancle and chronic artritis and would have been unable to work the land. However, with his skills, he could supply the area with tools and repairs.

The settlement mound is history in layers

The wilting rosebay willowherb swaying in the wind was hiding another trace, the farm mound. A settlement mound – previously known as farm mound – can be compared to a rubbish tip of house remnants, household waste and manure. Generations of houses and outhouses built on the same spot over the centuries created a distinct mound. The one at Elgsnes has not been examined by archaeologists, but many in the area have. They reveal layers from the Iron Age through the Middle Ages.

The Slayer of a Saint?

Mighty men resided at Elgsnes

A seal has been found in the farm mound, belonging to Nattulf Nattulfsson. He was a leading man in the area in the early 15th century, acting as a juror in court cases. A relative – we can deduce – Brynjulf Nattulfsson, was one of 12 leaders in Northern Norway who in 1420 wrote a letter of complaint to king Erik of Pomerania, who at that time was king in both Norway, Sweden and Denmark. He also participated in a military punitive expedition to the White Sea area that is now in Northerwestern Russia. This was a part of the ongoing conflict between the republic of Novgorod and Norway. In this period, the area was among the richest in the country, because of the rich cod fishing in the Andfjord. The Trondenes area thus paid more taxes than the whole of Trøndelag – Central Norway – at the time.

The hillfort looms over Elgsnes

Tore pointed up to a hill rising over the houses and fields of Elgsnes. Here, there are remnants of fortifications from different periods. In the Iron Age, this was possibly a hillfort for local defence. According to another theory, it was built in the Middle Ages to act as a refuge during Russian raids. Before the war, part of the walls were visible. However, during the occupation, the Wehrmacht built a radio direction-finding station here, and after the war, the Norwegian defence use the site as a radar station. There are thus no traces left.

Once, the water was much higher

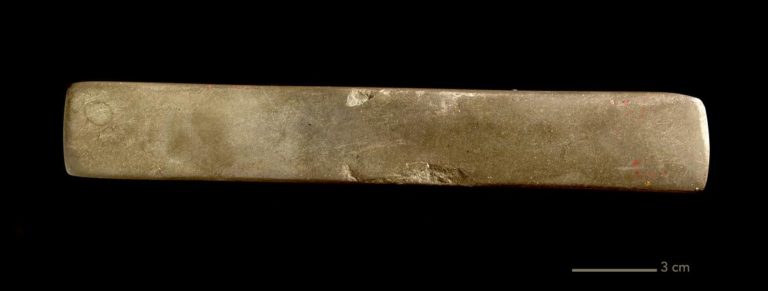

Some 7,000 to 5,000 years ago, the sea went all the way up to the road above the field. Until around 100 years ago, remnants of houses were visible in the landscape close to the forest, but they have since been lost to ploughing. In the area, one has found arrowheads, slate knives used to flense marine mammals, sinkstones for fishing nets and axes.

A walk through the forest finishes the tour

We finished our little walk around Elgsnes with a tour up the Øverlandet – “Upper land” – fields. The oldest find at Elgsnes was found here; a flake axe from the Mezolitic, some 10 000 years ago. This was a multi-purpose tool for scraping and cutting. Keep in mind that Øverlandet was a prime seafront location, as the water level was much higher at the end of the ice age. The last part of the walk is up to Durmålstuva hill, where there are several cremation graves from the migration period. From there. the forest path goes in twist and turns down to the fields again where an unopened grave mound from the Merovingian or Viking Age concludes the tour.

The landscape adds to the walk

All through the hike, Tore was an encyclopaedia of knowledge, easily switching from Stone Age through the Iron Age and the Middle Ages to 19th century fish trade. His interest goes back to potato harvesting among arrowheads, and already his grandfather and father had a keen interest in archaeology. The traces from the past are often invisible to the untrained eye, but with his knowledgeable explanations, everything comes to life. And the light birch forests, the green fields, the lovely beach and the view to the majestic peaks of Grytøya across the Toppsundet waterway, it is just beautiful and very scenic.

Good to know about

Elgsnes is on the tip of a peninsula north of Harstad, Northern Norway. It is about 40 minutes’ drive north of the city centre.

Go to the website of Visit Harstad.

You are outdoors for 1,5 hours. Wear sensible shoes to walk on the beach and along forest paths, and have enough clothes.

You walk about 1,5 km/1 mile, with many breaks inbetween. Most people can do it, but the area is not suited for wheelchairs.