Ruija – or Land by the Ocean – was where Finnish-speaking people from Finland and Sweden went when hunger gnawed at them, when unemployment threatened their lives and when new opportunities were needed. They were often well-received, because they were good workers, but they were also met with suspicion. Vadsø Museum – Ruija Kven museum is a rich exhibit on the Kven people. Their main exhibit is called Kohtamiinen Jäämeren kans – Encountering the Arctic Ocean – alongside the old NRK studio and a fun history of Vadsø in the foyer. Come in and explore!

Some call themselves Kven, others prefer Finnish-Norwegian

Vadsø Museum – Ruija Kven museum is dedicated to the ethnic group that came here from Finnish-speaking areas in Finland and Sweden from the 1700s onward. Kvenland was the term for this area on both sides of the Gulf of Bothnia, both on the Finnish side and on the Swedish side. Those who lived here were Kven, and they spoke the Finnish language of that time, known as Kven. When communications improved in the 1700s, Danish and later Norwegian authorities used the word Kven about those who immigrated. The term is now used for most people of Finnish heritage, especially in the oldest and westernmost areas. Some, however, feel that the word Kven has a negative connotation, and claim that it has been used as a slur. In Eastern Finnmark, some, but not all, prefer instead to refer to themselves as Finnish, or Finnish-Norwegian. The ties to modern Finland are also much stronger here. That is why the term Kven and Finnish(-Norwegian) are often used interchangeably when referring to this ethnic group.

60 faces welcome you

When you enter the exhibit, Kven or Finnish-Norwegian faces welcome you. There are sixty faces on the ceiling. Young and old from our time hang side by side with grainy black-and-white photographs. Some celebrities are among them, such as Leonard Seppala, who took part in the 1925 Serum Run to bring diptheria medicine to Nome, Alaska. Emelie Nilsen is an artist, from the Norwegian band Blacksheeps from Nesseby. Kristin Nikolaysen is a filmmaker from Alta. We realize that this exhibit is about people.

The Kven immigrated in waves

Contact between Northern Norway and the Finnish-speaking areas on the Gulf of Bothnia goes way back. The current Kven population can primarily trace their heritage back to several waves of immigration in the period 1700–1945. Trace the immigration routes on the museum’s map, which has lighted trails to show how they travelled.

The first wave came in the 18th century

In the earliest tax census from the 16th century, there is the odd Kven name here and there. The Great Northern War in 1900–1920 was fought between Sweden (Finland was under Swedish rule) and Russia. The war led to violence, hunger and plight in Finland. During this time, Kven moved to the lush river valleys in Northern Troms and Western Finnmark. Here, they were able to farm the land in much the same way they were used to from home. This migration continued until approx. 1820.

Migration moves east after 1820

After 1820, Finns and Kvens often moved in search of work. Northern Norway had a period of booming economic development in the 19th century. Fish exports expanded rapidly, especially from Vadsø, and mining operations were initiated in several places. There was work to be found. In addition, large parts of the Nordic region experienced crop failures in the 1860s, which further increased immigration to Eastern Finnmark. Many intended to continue on to America, because there were no direct boat routes to America from Finland. People normally worked their way north, and some stayed and settled in Eastern Finnmark. In modern times, in the 1960s and 70s, many Finnish youths found seasonal work in Eastern Finnmark’s fisheries. They discovered they were able to communicate with the locals in Finnish, so many didn’t leave.

Nation-building and new borders

The areas around the Gulf of Bothnia where most Kvens come from, fell under Swedish rule in the 14th century. In 1809, Finland was established as a Grand Duchy under Russia, and a border between Sweden and Finland was drawn. In 1826, the borders between Norway, the Grand Duchy of Finland and the Tsardom of Russia were drawn. In the late 19th century, nationalism was a strong trend in both Norway and Finland. Norwegians worried about the so-called “Finnish Danger”. There were fears that Finland would conquer areas where many people spoke Finnish. This led to suspicion against the Kvens, and there was a heavy emphasis on Norwegianization in schools and from public authorities. Norwegianization efforts were especially strong in the 1930s.

Outfields a source of fuel and food

The museum also shows how Kvens used nature. They cut the outfields to gather grass for the animals, from marshes and fields. They cut wood, and in areas where there are no tress, they gathered birch rods from dwarf birches. In the inland valleys, they cut pine trees for sale, and they burned tar. The people in Reisadalen were called “tervalantalaisia” – or “Tar Kven”. They harvested peat from marches, dried these and used them as fuel. They gathered driftwood for use as fuel and building materials. Most of these activities are much too small-scale to bother with today, and the landscape grows differently.

The Kven were a farming people

In Northern Finland, cereal farming is common. The Kven continued these practices in the valleys with relatively warm summers, such as Alta and Nordreisa. In Varanger, where the climate is less forgiving, their farming practices mostly consisted of animal husbandry and subsistence potato farming. Most of the farm work was performed by women, because the men went out fishing. The Kven were also good with horses, and used them for both farming and transport.

The Kven learned open sea fishing in the Land by the Ocean

Some of the first Kven who came to Eastern Finnmark from Finland, came here a seasonal workers in the fisheries. The Varanger Fjord is rich in fish, and more hands were needed. Soon, the Kven learned both how to fish and how to build boats. Vadsø was a major exporter of fish, to both Western Europe and areas in Northwestern Russia. The Pomor trade between Northwestern Russia and Northern Norway dates back to the 18th century and lasted until the Russian Revolution. In Vadsø, fishing eventually took on a more industrial scale, with Svend Foyn’s whale oil, cod liver oil and later herring oil factories in the latter half of the 20th century.

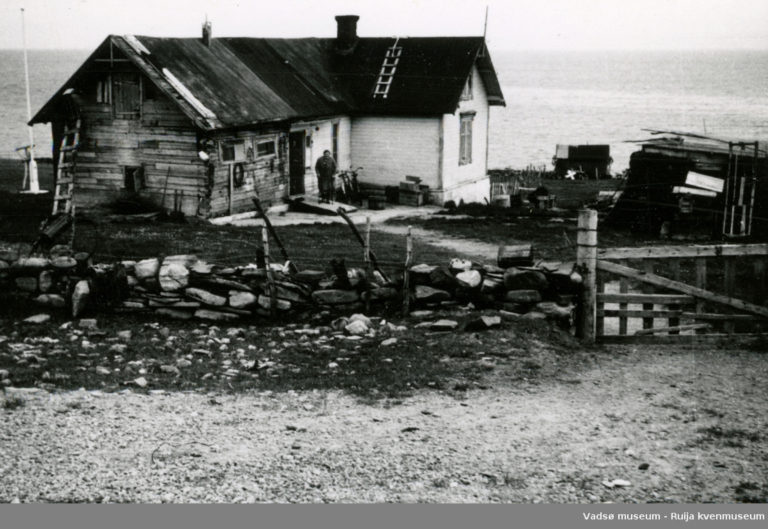

New building customs developed in the Land by the Ocean

The Varanger house is a special type of house, developed in Eastern Finnmark, based on traditions from Finland and Northern Sweden. The house and the barn are built together, so people don’t have to go outside on cold winter days. Several of these buildings have been preserved in Varanger, as this area was not completely destroyed during the war. Of course, a sauna is also a must, and the communities often had a communal sauna shared by all. They used to light it for the women on Fridays and for the men on Saturdays. In the museum, you get an opportunity to join the conversation in Vadsø’s Dolonen Sauna.

Clothing and rugs were home-made

The clothes worn by the Kven were homespun. Frieze for outerwear, mittens and hats, underwear and shirts – making clothing was women’s work on winter nights. Rug weaving was a common practice among the Kven, and the rugs are on the floors of the museum. Kven clothing customs did not stand out from the other ethnic groups in the area, and in many places they dressed like the Norwegian coastal fishermen, and in some communities, they wore traditional Sami clothes. Today, a Kven costume has been developed, using elements from both Finnish customs as well as some modern tweaks. This costume is not a copy of something old, it is a modern interpretation.

Kven is a language closely related to Finnish

Kven is recognized as a minority language in Norway. In the western areas, they speak a langauge that the Finnish-speaking people of today find old-fashioned, with incomprehensible loand words from Norwegian. Even so, Kven is mutually intelligible with Finnish, for the most part. The language in Eastern Finnmark is much closer to modern Finnish, and conversations flow much easier. This is because they are able to get Finnish radio and television, and there is much more frequent contact across the border. Modern Kven is a standardized written language, a true language in its own right. Some still call it Finnish, because they like to point out the obvious kinship. Try your hand at Kven in the museum’s monitors, and maybe learn a little bit of the language.

Mirror wall shows Kven last names

Some of the most striking feature, especially for visitors from Northern Norway, is the wall with all the last names. In the western areas, most have Norwegian last names, like Jensen and Berg. In Eastern Finnmark, however, where the settlement history is shorter for most people with Kven heritage, many of the name have a Finnish ring, such as Tapio, Bellika, Dikkanen, Rauhala. The spelling is different from modern Finnish and Kven standards: Gulmælæ and Kivelæ, for example, to avoid the complicated ä, which is not used in Norwegian, and Wara, to get a more distinguished sound. In modern Finnish and Kven, these would be spelled Vaara, Ås. Wickstrøm and Kolstrøm are examples of Swedish-sounding names – Swedish last names are not uncommon Finnish-speaking areas in Finland and Northern Sweden. This wall gets everyone with a connection to Northern Northern Norway talking: “I know someone who…”.

Listen to Kven tell their stories

On the monitors, you can also listen to Kven tell their stories. Three older people from different parts of the Kven areas, talk about the old, traditional life. Three younger people talk about what it is like to have a Kven identity in modern Northern Norway. Modern-day immigrants are also features, with a woman from Oulu who came to Finland in the 1960s, and immigrants from the third world.

NRK Finnmark was supposed to represent the Norwegian language in Finnmark

The museum is located in the old studios of NRK Finnmark. NRK is the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. Why Vadsø, and not Hammerfest, for example, which was a bigger city? The reason is because Vadsø is part of a distinctly multi-ethnic area. In the nationalist 1930s, they questioned people’s loyalty if they listened to Finnish radio and spoke Kven at home. NRK was established in Vadsø in 1934 and provied broadcasting in Norwegian. The official Norway was available in the ether. The office changed its policy after the war, however. From 1946, news were provided in Sami, and from 1970, they even provided broadcasting in Finnish.

Vadsø’s history rolls across the table

Vadsø Museum – Ruija Kven museum starts in the foyer, with clever story-telling. A table serves as a monitor, with a map of Vadsø. We start in the late Middle Ages, with a little fishing village built with the houses close together, and a church on Vadsøya. You can still see the foundations of this. The village then moves to the mainland. From 1833, Vadsø becomes a market town, and the great migration of the 1860s causes the city to expand. Industry eventually finds its way back to Vadsøya, and we can see the shoreline begin to creep outward. It’s very clever – you get an instant overview, and then you watch it again just to enjoy it.

Vadsø Museum also has other exhibits

After being introduced to Kven culture in the Kven museum, you can explore Vadsø’s history. Tuomainen building is a well-preserved, protected farm with a unique bakery oven that is still in frequent use. The nearby Esbensen building is a Norwegian merchant home. Both were originally built as Varanger houses. The Bietilæ building is a protected tenement house, with a pier, boat slip and several outbuildings. The buildings were used for fishing and fish processing. The Kjeldsen plant on Ekkerøy outside Vardø is a former fish processing plant, shrimp factory and train oil factory, which also housed a grocery store. Ytrebyen – the outer city – is on the east side of the city centre, whereas Indrebyen – the inner city – is on the west side. The city centre was destroyed by bombing in 1944, so if you are interested in exploring the history, you will have to move to the outskirts. If you are up for a little walk, wander across the bridge to Vadsøya to take in the airship mast and the culture trail around the oldest parts of Vadsø.

The Ruija Kven museum is for everyone

The Ruija Kven museum is a modern museum. Press buttons and watch migration routes, listen to people talk and learn some Kven words from interactive monitors. We recommend walking around on your own, watching photographs, pressing monitor buttons and taking in the information. The more analytically-minded will find smart texts on the monitors that are both simple and informative, with a deep understanding and respect for history. All of the text is provided in Kven, Norwegian and English. That makes this a place where the Kven heritage is prominent. The value of the Ruija Kven museum is far more than a mere tourist attraction – anyone with Kven/Finnish heritage in Northern Norway can come here to learn more about their own history. For a small ethnic group, that is a big deal.

Good to know about Ruija Kven museum

Ruija Kven museum is found in the small city of Vadsø, a couple of blocks from the main street, in the old NRK (Public broadcasting) house.

This somewhat antiquated term used in Northern Finland and adjacent areas of Northern Sweden means Land by the Ocean. It roughly corresponds to the two northernmost counties in Norway, Troms and Finnmark.

Ruija Kven museum is open six days a week all year, with the exception of some public holidays. Consult their website for updated information.

Kven was originally used about Finnish speaking people along the Gulf of Bothnia, both in today’s Finland and Sweden. When people started to emigrate from this region to Northern Norway in the 18th C., the Dano-Norwegian authorities started to use the term Kven about the newly arrived. Today, many in this ethnic group consider the word Kven the best and most correct.

Three old houses are part of Vadsø Museum. The Tuomainen compound, the Esbensen house and the Bietelæ compound. The airship mast at Vadsøya Island are part of the story of the airship expeditions of “Norge” (1926) and “Italia” (1928) to the North Pole. There is also a historic path to marked ruins of the oldest Vadsø from the late middle ages.